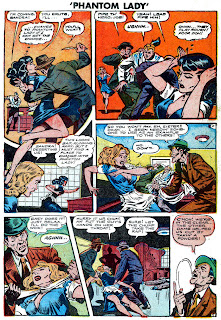

Syd Shores did this violent crime story for Wanted Comics #48 in 1952. Shores was a very facile and talented comic artist, one of the journeymen I admire who had been around since the earliest days of comics. The symbolic splash for “The Man With Nine Lives” is very striking. Like the best artists Shores didn’t stick with one genre; he could draw just about anything. I have examples of him doing horror and Western, also (see the links below my short article on Fredric Wertham and Alfred Hitchcock).

**********

Wertham and Hitchcock

After Dr. Fredric Wertham, M.D., had done serious damage to the comic book industry in 1954 he didn’t just go away and retire. He was available to the legal system and reporters on the subject of media violence. For Redbook magazine Wertham interviewed director Alfred Hitchcock on his movie, Psycho. Psycho had been linked in the newspapers to at least a couple of murders where the killers were reported to have been “inspired” by the film.

From Alfred Hitchcock and the Making of Psycho by Stephen Rebello, published in 1990:

“. . . Hitchcock agreed to talk with psychiatrist, Dr. Fredric Wertham, an author and outspoken critic of media violence. The published account of their dialogue suggests that Hitchcock was not about to be pinned down. Wertham, after admitting that he had not seen Psycho [emphasis mine], tried several times to get the director to admit that the violence in the film was ‘A little stronger than you would have put in formerly — say ten or fifteen years ago?’ Hitchcock replied, ‘I have always felt that you should do the minimum on the screen to get the maximum audience effect. Sometimes it is necessary to go into some element of violence, but I only do it if I have a strong reason.’ Wertham persisted: ‘But wasn’t this violence stronger than your usual dose?’ Eventually, Hitchcock conceded, ‘It was.’ ‘More?’ asked Wertham. ‘More,’ Hitchcock replied. So it went for Wertham, and one suspects that is was, for him, much like dealing with a particularly defensive patient.

“The psychiatrist may have hoped to elicit from Hitchcock at least an artistic, if not moral justification for that violence. Yet one is left with the clear impression that Hitchcock might justify the bloodletting in Psycho similarly to the way he had justified to François Truffault the risqué opening scenes. ‘Audiences,’ Hitchcock said, ‘are changing. I think that nowadays you have to show them the way they themselves behave most of the time.’ Thus, the filmmaker implied that he was a reporter, not a shaper, of human behavior.”

Here Wertham showed that he didn’t need to see what he was criticizing in order to criticize it. Isn’t this a lot like pressure groups that jump on pre-release publicity of books or movies in order to justify their calls for censorship or banishing — or even death to the author?

By calling in Wertham as their interrogator Redbook showed it had its own agenda. Wertham was famous for his views on violence in popular culture, comic books, television and movies, so the magazine was out to show their readers that Hitchcock was responsible for the evil wrought by his movies. With that in mind, why would Hitchcock agree to sit down with Wertham?

Hitchcock had a strongly intuitive knowledge of psychology. He was a master showman (think P.T. Barnum) and manipulator when it came to moving his audiences through the story. The psychology that Wertham used to come to his conclusions about violence being promoted by popular culture was also used by Hitchcock in the way he brought audiences into theaters and juggled their fears and emotions. I would not doubt that Hitchcock felt such an interview, even with someone who had such well-known and outspoken views as Dr. Wertham’s, could be turned to Hitchcock’s advantage.

One thing both of them had in common was the ability to rise above the din and clamor of everyday life — and the news cycle— and make themselves heard. The difference is that after Hitchcock died he became an even bigger cultural icon than he had been when he was alive, where Wertham sank into public obscurity, except amongst us Golden Age comics fans.

I have done several posts where Wertham fits in. To find them click on his name at the bottom of this post.

**********

As promised, two more stories by Syd Shores. Just click on the thumbnails.